- Home

- Una LaMarche

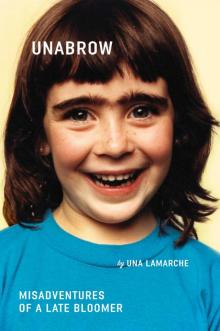

Unabrow Page 3

Unabrow Read online

Page 3

The kimonos (along with molting feather boas and floor-length nightgowns) were relics from my own mother’s days as an urban bohemian, back when she traipsed across continents in platform boots and a rabbit fur coat, making abstract, labia-shaped sculptures and running into Rudolf Nureyev outside Studio 54. But after years of dress-up use, they were wrinkled and threadbare and bore the faint but unmistakable odor of cat piss. I didn’t care. I accepted the pee smell as part of the journey to motherhood and simply imagined, as I tied on my birthing robe, that it was my signature sachet.

After stuffing my chosen spawn against my ribs, I would contort my tiny body in theatrical pain and hop up and down until my “baby” fell to the floor with a thud. My children were as diverse as they were synthetic. I gave birth to Cabbage Patch dolls, to sad-eyed Pound Puppies, and to fully dressed Peaches ’n Cream Barbies, who looked like sherbet-colored jellyfish crossed with Tammy Faye Bakker.

Ever the nurturer, I would “feed” my babies by pounding their heads against my concave chest or by smearing peanut butter across their faces like war paint. And after a few minutes, when I inevitably tired of parenthood, I would toss them in the pee basket with the cat and go have a snack.

You know, just your average six-year-old’s birth story.

A woman’s relationship with her body is based on such an advanced amalgam of math, physics, and behavioral psychology that I don’t think anyone would pass it if it were a written test. It couldn’t be standardized anyway, since everyone’s equations are totally different. Even just to get the numbers you’re working with, you’d have to calculate things like:

(cultural standards of beauty [culture you’re from] / cultural standards of beauty [culture you live in]) × (waist-to-hip ratio / pie [in pounds, consumed so far in lifetime]) = objective attractiveness

objective attractiveness / (number of awesome and loving relatives/mentors/lovers − number of manipulative and/or abusive/dickish relatives/mentors/lovers) × total lifetime exposure to Angelina Jolie’s face [in minutes] number of Facebook profile photos you’ve taken of yourself = subjective attractiveness

subjective attractiveness × (number of years of formal education / number of seasons watched of America’s Next Top Model) = gross confidence

subjective attractiveness × gross confidence / number of current fashion/lifestyle magazine subscriptions = net confidence

See? Gah. Already too much math, and we haven’t even added in crucial factors like age, income, relationship status, the ability to pull off bangs, or that pair of pleather jeggings you may or may not have bought after a three-mimosa brunch.

Please understand that I’m not trying to make light of the serious, worldwide epidemic that is the commodification, sexualization, and simultaneous hatred of women’s bodies. It’s disgusting and depressing, whether you’re talking about the politics of reproductive rights or the kind of hormone-laced-corn-fed culture that leads eight-year-olds to menstruate and kindergarten girls to dabble in anorexia. But these are the times we live in; body dysmorphia is the new black. I can write an entire chapter based on the breezy assumption that most women—if not most humans—hate their corporeal forms on some level, no matter where they fall on the body mass index spectrum. Amirite, laydees? Ugh, Jesus, let’s just have a drink and get on with it.

Anyway, once upon a time, long ago and not at all far away since I still live six blocks from where I grew up, I can vaguely remember being nonjudgmental about my body. This was back in my birthing kimono, salad days, when I marveled at what my body could do—or at least pretend to do—as if I were the only person alive who had attempted such heroic feats as leaping from the coffee table onto a pile of couch cushions, sliding down an ice-covered stoop on my butt, or swinging so high and fast at the playground that the support beams shuddered.

I had a lot of insecurities as a kid. I was sort of unspecifically scared most of the time, even when—or, come to think of it, especially when—I was doing things that were supposed to be life-affirmingly, pants-shittingly fun for people in my age group. For example, since we lived in New York my parents would take me and a friend or two to the Big Apple Circus every year. Unlike the big, corporate Barnum & Bailey game, the Big Apple was a cozy affair with a single, European-style ring where clowns would often invite people from the audience to participate in things like throwing pies and helping a small dog to ride a unicycle. Sometimes performers would squirt water at us or try to sit in our laps. All of these possibilities terrified me to the point where I couldn’t even pay attention to the acts because my brain was too busy calculating how I might quickly find an exit door or spontaneously self-immolate in the event that I was pulled onstage in front of thousands of peanut-chomping hecklers who might not see the delicate beauty my parents saw in my oversize Bart Simpson T-shirt, Technicolor stirrup pants, and jauntily crossed front teeth. So I was a panicky preteen, yes. But my fears were never rooted in my body.

That all changed when, at age twelve, my mother gave me the classic puberty manual What’s Happening to My Body? I’m not saying this sensitive maternal gift was a curse or anything; however, curiously it was exactly around this age that my physical being began to betray me. From birth to age eleven, my body had been just that—a body. The thing that moved me from place to place and let me climb jungle gyms and eat french fries and make up totally unironic interpretive choreography to the Dirty Dancing soundtrack with my cousins. My skin fit perfectly and it never even occurred to me to look critically at the real estate below my neck. The only embarrassing thing that my body did, as far as I was concerned, was fart—and even that was kind of funny if correctly timed.

But then, the summer I was twelve, I grew breast. That’s right: breast. Singular. I’ll spare you the details, except to say that was also the summer I spent at a Quaker sleepaway camp with communal showers. And making matters worse, I was hairless but for my legs, which had somehow sprouted twin sea-otter-like pelts—seemingly overnight—and for my forehead, where I was cultivating a unibrow that would make Anthony Davis do a spit take (see page 4).

I had become suddenly, visibly, painfully pubescent, and the book helped reassure me that I was normal, which was a tough sell seeing as my only previous exposure to illustrated genitals was the R. Crumb anthology I’d paged through as a four-year-old in my bachelor babysitter’s Upper West Side apartment, mistaking it for a children’s book. (Incidentally, the same babysitter and I would later make up fantasy stories about Ronald and Nancy Reagan visiting a fantastical place called “Big Butt Island.” I’m pretty sure my parents didn’t pay him anything extra for these invaluable lessons.) Anyway, poring over those line drawings of puffy aureoles and patchily haired testicles, I turned a corner and came of age. My body morphed abruptly from a utilitarian vessel to an untrustworthy stranger.

THE SEVEN STAGES OF CORPOREAL METAMORPHOSIS FOR HUMAN BEINGS—OR MAYBE JUST WOMEN? I DON’T KNOW, BUT THIS IS STILL VERY SCIENTIFIC, I PROMISE

I. Body as Magic

Although I have come close to replicating it with certain pharmaceutical substances, I don’t remember this stage firsthand. So it’s lucky that I’ve been able to study and rediscover the mind-blowing period of early physical consciousness through my son. This encompasses the first two years of life, give or take, when every single thing the body does is trippy, primal, and existential in the purest meaning of the word. An abbreviated chronology of this stage can be summarized by the following inner monologue:

What?! CHECK ME OUT! I am here. I can see things! I can hear things! I can make sounds! Whoa, I have toes! I think I can fit them in my mouth! Ahhhhh, fingers! Must touch everything. Must. Grab. EVERYTHING. What else can fit in my mouth? Sitting! Sitting upright!!! Who is that in the mirror? Who is that marvelous creature? Will he mind if I give him a sloppy kiss? No, he doesn’t! He’s KISSING ME BACK! OMG, OMG, I’m crawling!!!!!! Now I’m standing!!!!!!! WALKING, SUCKAS!!!!!!!!!!!!!! NOW I’M

RUNNNINGGGGGGGGG!!!!!!!!!!!!! CLIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMBING!!!!!!!!! Nothing can stop me now! Look out, world . . . and small house pets!

II. Body as Vessel

This is the aforementioned period of unwitting bliss during childhood (typically age three to about ten or eleven, if you get lucky and don’t have any physical disabilities and/or body-shaming adults in your life) when the body is completely disregarded, assuming it can perform all its basic functions without incident. Sure, you might want to be able to jump higher or hit a baseball farther or learn to cartwheel, but you never look at your legs and think, God, my thighs are like Easter hams! I have to start doing Pilates! Instead, you look at them and think, Legs. Because that is all they are. And then you use them for their intended purpose, which is to kick your brother.

III. Body as Stranger

Perhaps, like me, you grew a single breast or had the kind of unfortunate hair growth pattern that prompted the most popular girl in your seventh grade class to ask, “Do you shave just the backs of your legs?” during lifeguard training. Or maybe one day in social studies, you found yourself searching the room for the source of a pungent, sour milk smell only to realize with horror that the call was coming from inside the house—or, more specifically, from inside your shirt—and that deodorant was about to become a priority in your life, second only to examining your pubic mound every night for new hairs. Whatever it is, these first awkward whiffs of puberty (usually around age eleven or twelve) catapult your physical being into a strange new universe of significance. The body, once a steadfast, invisible ally, is now a dangerously loose cannon gunning for the spotlight. Cystic acne, fat deposits, an ill-timed erection—any of these could befall you at any time. You would sleep with one eye open if you weren’t so exhausted from the twice-daily full-body washes you must endure to control your new hormonal stench.

INTERMISSION: A REAL DIARY ENTRY THAT I WISH WERE FAKE

August 16, 1994

GUESS WHAT?! I got a tampon in. I thought I was defective and had two orifices or something but NO! YAY! I am so proud and relieved. Let us mark this day in history!

Much love, Una

I am not kidding when I say that this was by far the most exciting entry my diary had ever seen up to that point. Had I started to write my autobiography in 1994, the Great Tampon Victory would surely have been the highlight, deserving three or four chapters. The rest of this volume, which spans the summers of 1993 to 1997, recounts my days in the way that your ninety-year-old great-aunt might: Let’s see, I had breakfast—grapefruit—and then I watched that Geraldo on TV. I read for a while and went to the pharmacy for my Coumadin. We had hamburgers for supper. I peppered my writing with declarations of love for unrequited crushes, but I never had so much as a study date to write to my diary about. I can only imagine that my all-caps GUESS WHAT?! elicited my jaded diary to respond, What, did we fall asleep reading John Grisham and dream about Evan Dando again?

In my defense, I later had a boyfriend who began his diary entries with the words “Dear Jesus,” so it could be worse.

IV. Body as Object

This stage, I think, is felt most acutely by women. Once you make it through the craters of puberty (this age differs for everyone, but a good rule of thumb is to find the page in your parents’ photo albums in which the photos resume normally after a series of years in which they have been crudely defaced with marker or ripped out in order to be ritually burned) you will be understandably insecure. Your body has up and Scooby-Doo’d you, pulling off its kindly mask to reveal a villainous wretch. And it is just when you are getting used to the new you—the taller, curvier, muskier you with boobs and hips and more places to shave—that adults begin to notice you in new and unwelcome ways. This is the phase during which catcalls will come into your life, but since you are still technically a girl, not yet a woman, to paraphrase Britney Spears, they will mystify you at first. Eventually, they will come to humiliate you, and make you want to retreat into the safe, smooth, flat planes of your child body, which brings me to the next stage.

V. Body as Nemesis

It’s Very Special Episode time; bear with me. This one is going to be longer and more poignant. It’s like the Sweeps Week of this list. I even have celebrity cameos!

I’m going to speak for myself, and not pretend I’m representing all of womankind, mostly because I still harbor a deep-seated but dubious hope that I represent the exception and not the rule. For me, coming out of puberty (or, really, out of teenagehood, because I was and continue to be a late bloomer) dovetailed with starting to view my body as my enemy, which spiraled into an eight-year battle with anorexia and bulimia.

I know. Not two hundred words ago I was writing about Scooby-Doo and Britney Spears and now we’ve taken a detour into my most painful secrets. It’s weird for me, too, and I’m really uncomfortable letting that just sit there without a self-deprecating joke to soften it. But there’s nothing funny about eating disorders, and I’m not going to pretend that there is. Remember that FX comedy series Starved, about an eating disorder support group? Right, neither does anyone else. (And this is FX! The channel that built an entire episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia around seeing Danny DeVito take a dump on the floor of a bar! If there were anything uproarious about bulimia, surely FX would have discovered it.)

So, this unhappy stage—which doesn’t affect everyone and which definitely does not automatically include eating problems—can last a long time. Chances are, once you get accustomed to your flamboyant new adult body, you begin to target perceived flaws. You might look at yourself and think, How can I be prettier? How can I be more desirable to the people of whatever gender I lust after? How can I get noticed? Or you might have the opposite reaction: How can I become invisible again? How can I get back into a body that doesn’t betray me or attract unwanted attention on a daily basis? Unfortunately, the answer to all of these questions is usually the same: lose weight. Because that is the enormous mind-fuck that our culture has succeeded in selling across all racial, political, and socioeconomic lines: that the taut flatness of prepubescence represents the height of both sexual desirability and asexual innocence.

I wish I knew how to skip over the Body as Nemesis stage. For me, it took a lot of therapy, practice, and false starts, as well as the acceptance that I should never, ever buy another pair of capri pants, not even on sale, if I ever want to really love myself the way I truly am. But one hard-and-fast rule I have walked away with is this: don’t read lists of other people’s daily calorie intakes.

You’d think this would be an easy enough thing to avoid, but if you look around, they are everywhere. Magazines just love to ask celebrities what they eat in a day. Unless the celebrity in question is a hot-dog-eating champion, there is no way to pretend this is news, so instead they try to pass it off as either (a) an aspirational primer for those mere mortals who can’t afford to stock fresh wild salmon and/or make their own cashew butter or (b) a refreshing peek at a “totally normal” glutton who is “just like us” except also impossibly toned and mind-bendingly gorgeous despite his or her deep-dish stuffed-crust Domino’s habit. Do not buy into these lies. There’s no way the person is telling us everything. I mean, look, Gwyneth Paltrow has built a brand for herself as a cheerful, macrobiotic foodie based on the implicit assumption that she has never found a Skittle under the stove, wiped it off on her pants, and then eaten it. But everyone has at some point in their lives done this exact thing, so do the math, Gwyneth.

P.S. In my early twenties—during the height of my illness—I used to fantasize that if I were ever granted powers of invisibility (this was right around the first Lord of the Rings movie), I would use it to follow around skinny celebrities and find out what they really ate all day. Yes, you read that right; I decided to use my hypothetical superhuman powers not for good, or even for middle-school revenge-based evil, but for the kind of research task that might be delegated to a summer intern at Shape magazine.

VI. Body as Magic, Part 2

By the time you’ve lived in your body for thirty years or so, there’s not much it can do to surprise you anymore. All its sounds and smells and unsightly bulges have been cataloged and then either frantically hidden or hopelessly ignored. Which makes it all the more shocking when your body up and does something you never thought possible. Which, in my case, was to make a cuter, littler body inside of mine. In 2011, I became a human version of Hasbro’s Puppy Surprise doll, a bucket list goal I had been gestating since the mid-1980s.

Not everyone’s magic is childbirth. Obviously I’m excluding half of the population outright,* and plenty of women decide either not to have children or to have them via adoption or surrogacy. But I’ve heard similar stories from marathon runners, disease survivors, and, memorably, a backup dancer from Madonna’s Sticky & Sweet tour (of whom I am insanely jealous). Something incredible happens when you endure a grueling physical challenge, either by choice or by fate. It changes your body, and your relationship to your body, forever.

Since I am lucky enough never to have suffered a major illness or been forced to run more than fifty feet in my adult life, I’m here to talk about the transformative experience of baby making. There’s nothing else remotely like it, and even making up an analogy ends up sounding ridiculous. Like, imagine for a moment that puppies grew in fanny packs. If you wanted a dog, you’d get this bulky, retro, flesh-colored albatross to hang around your waist (let’s say it costs a thousand dollars, which is probably the minimum you’d spend on prenatal care even with insurance) and then you’d lug it around with you at all times for nine months while it got heavier and heavier. People would constantly exclaim over the fanny pack and rub it affectionately, and then they’d give you an ice-cream sundae and instruct you to go to town. But one day, the fanny pack would burst open and a needy puppy would leap out and immediately shit on you, and then you’d have to chase it around until you died. I kind of don’t think anyone would get a dog under those circumstances, do you?

Like No Other

Like No Other Five Summers

Five Summers Don't Fail Me Now

Don't Fail Me Now You in Five Acts

You in Five Acts Unabrow

Unabrow