- Home

- Una LaMarche

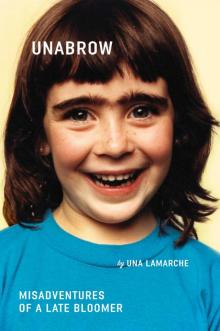

Unabrow

Unabrow Read online

A PLUME BOOK

UNABROW

Photo by Jeff Zorabedian

UNA LAMARCHE is a writer and unaccredited Melrose Place historian who lives in Brooklyn with her husband, son, and hoard of vintage Sassy magazines. She is the author of two young adult novels, Five Summers and Like No Other, and remains a member in good standing of the Baby-sitters Club Fan Club. Lena Dunham once favorited one of her tweets.

Praise for Unabrow

“This book had me laughing out loud on every page. Una LaMarche has mastered the art of self-effacement.”

—Mara Wilson, actress and author of (K) for Kid

“Una La Marche owns up to everything you probably still wouldn’t admit—and she does it with laugh-out-loud style.”

—Amy Wilson, author of When Did I Get Like This?

“Una LaMarche is a delightful writer: funny, irreverent, with a sweet, good heart underneath it all.”

—Sara Benincasa, author of Agorafabulous!

“After spending my life believing I was the only freak ever to have one boob grow in months before the other, along comes Una LaMarche to let me know I was never alone. For anyone who’s ever eaten an elderly piece of candy found under the stove, or who is still upset that Billy and Alison never got married on Melrose Place, you will recognize yourself in these pages. Part confessional, part manual, Unabrow is all hilarious.”

—Caissie St.Onge, co–executive producer of Watch What Happens Live!

PLUME

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2015

Copyright © 2015 by Una LaMarche

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

LaMarche, Una.

Unabrow : misadventures of a late bloomer / Una LaMarche.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-15566-4

1. LaMarche, Una. 2. LaMarche, Una—Childhood and youth. 3. Young women—United States—Biography. 4. Mothers—United States—Biography. 5. Coming of age—United States. 6. Popular culture—United States—Miscellanea. 7. Conduct of life. I. Title.

CT275.L25285A3 2015

306.874'3—dc23

2014021212

Cover design: Zoe Norvell

Cover photo: Will van Overbeek

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

Version_1

CONTENTS OR, A CHRONOLOGY OF ERRORS

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Author’s Note

Unabrow

What’s Happening!! . . . to My Body?

A Scar Is Born

Death Becomes Me

Sissy Fuss

Late Bloomer

Rules for Sitcom Living

Achilles’ Wheel

Shopping for Godot

Designer Impostor

Free to Be Poo and Pee

Gullible’s Travels

Drinks on Me—No, Literally, on Me

Gratuitous Foodity

Sacrilicious Expired Easter Cake

Tootsie Roll Log Cabin

Blank Canvass

I’m Not a Girl . . . Not Yet a Golden Girl

You Betta Work

I Love You Just the Way You Aren’t

How to Be a Perfect Parent in Five Easy Steps, or Never

Book Club Cheat Sheet

For Sam

(Someday, this will explain a lot.)

Your life story would not make a good book. Don’t even try.

—Fran Lebowitz

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are probably hundreds, if not thousands, of people who I need to thank for helping this book come to fruition, because based on my understanding of the ramifications of time travel (which itself is based on repeated viewings of Back to the Future and Back to the Future Part II), every single decision and human interaction of mine up to this point has gotten me where I am today, and if I were to go back and try to change even the most minuscule detail, like, say, to urge my seventeen-year-old, prom-bound self to reconsider her unintentional geisha makeup and the case of Zima she would later drink in a stranger’s hammock, then I might come back to 2015 to find myself missing limbs, or working on a cruise ship. So thank you to everyone I have ever met, bumped into, or ducked into an alley to avoid.

A few, however, deserve special mention. In rough chronological order: Thank you to my parents, Ellen and Gara, for bringing me into the world, fostering my twin loves of writing and excessive TV watching, and continuing to support me even after it became clear that I would probably write a book about you later in life; to my beloved sister, Zoe, for putting up with my diva behavior on family road trips, keeping me sane(ish) for twenty-seven years and counting, and agreeing to take care of my facial hair should I ever find myself on life support; to my extended family (both blood and marriage) and my incredible friends, for their encouragement and enthusiasm; to my inimitable agent, Brettne Bloom, who changed my entire life with a single e-mail, and who worked tirelessly with me to get a proposal into shape; to my amazing editor and biggest cheerleader, Becky Cole, for making me feel witty and hilarious while simultaneously seeing all of my crutches and flaws with a gimlet eye and gently plucking them out like stray eyebrow hairs; and to the fantastically talented editorial and production team at Plume, for making this book everything I ever hoped it could be.

Finally, to Jeff and Sam, the loves of my life: without you, I am nothing. This book is for you. You may also share it with your future therapists in the interest of saving time. (You’re welcome!)

INTRODUCTION

When we were three, my best friend Salvador and I used to play a game we called “look in butt.” It was doctor, essentially, but as we had no interest in heartbeats or hearing tests, we chose to focus solely on the anus. One of us would bend over and the other one would conduct the examination. What we were looking for, I can’t say—stray He-Man figures? lost crayons?—but we took our work seriously.

For years afterward I assumed that look in butt was consensual—the only thing that tempered the humiliation of its existence was Sal’s complicity—but my father finally broke it to me that he’d overheard us playing it once, and that Sal, as he’d removed his underwear, had turned and said to me gently, “Una . . . this is wrong.”

My small, naked friend’s words have echoed in my head countless times since—when I attempted to fracture my own ankle in order to get out of track practice; as I was trying on my first boss’s ten-year-old daughter’s shorts while alone in their apartment; when I opened my colle

ge minifridge to reveal nothing but a bottle of gin and a carton of milk, and I thought to myself, Well . . . why not?—but they haven’t made much of a dent in my track record of personal shame and flawed judgment. “Una . . . this is wrong,” I’ll think. But then I’ll do it anyway because, sometimes, you can’t tell what the right thing is until you do the wrong thing. And the silver lining about missteps is that they can set us on a better path. We examine them closely and try to come away with something, if not profound, then at least enlightening.

In August 2009, I was newly married and still on birth control but had the poor judgment to watch the movie My Life while drinking a bottle of vinho verde. For those unfamiliar with the plot, it’s a 1993 Michael Keaton vehicle about a man with terminal cancer who makes instructional videos for his unborn son. The poster shows a baby’s hand reaching out for a grown-up hand, and the tagline is “Don’t watch this movie with someone who is made uncomfortable by hysterical weeping.”

I decided that I should start keeping a list of lessons for my future children, not only in the case of my untimely and extremely heart-wrenching demise, but also just, you know, in case I got lazy or forgot. I had done a study on memory in college and learned that every time your brain accesses a long-term memory—say, that time you tried to somersault off the top bunk into the laundry basket—it gets altered slightly before it’s filed away again, so that, little by little, stories change, and their morals get murkier. I wanted to get all my hard-earned wisdom down on paper before it faded into the abyss of my consciousness, replaced by plotlines on Girls and the words to early ’90s rap songs. (That said, this book references both Girls and early ’90s rap songs, because I know my strengths.)

Even though I wrote these essays, charts, and lists with my future grown-up children in my mind’s eye, please do not give this book to an actual child unless he or she shows signs of premature jadedness and is able to use the word “fuck” at least three ways in a sentence. This book is for adults only—although that makes it sound like there’s a lot of sex in here, which there’s not.

I wrote this for my fellow women and mothers, but also for dads, dudes, trans people, precocious teenagers, octogenarians who refer to themselves as “pistols,” and anyone who can barely take care of themselves. Peace, love, and metaphorical brotherhood are all nice ideas, but I think what unites us as a species is that we all have cringe-inducing memories that we vow never to tell anyone and never to let anyone else repeat. Oops.

XO Una

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This collection, contrary to the sage words of Fran Lebowitz, quoted previously, is largely a work of memoir, so obviously I have to write this disclaimer now that we live in the post–James Frey era in which every nonfiction writer lives in fear of being slowly shamed to death and/or drowned in his or her own sweat on live television. Just so we’re clear: Everything happened as written to the best of my memory, which is to say, hampered somewhat by copious amounts of red wine and way too much exposure to pop culture in my formative years (I can give you the full name of every character on the original Melrose Place but do not know my blood type or my grandmother’s birthday). I changed a few names here and there to protect people’s privacy, and had to fill in some details using the similarly wine-addled brains of family and friends, but there’s no straight-up lying. You’ll notice, for example, that nowhere in this book do I mention having once thrown marbles out a window at Joe Cocker, because it was actually my friend Anna who did that, not me, despite what I have been telling people for the past fifteen years.

Unabrow

My sister, Zoe, and I have this agreement that if I ever fall into a coma, she will come to the hospital every few days to visit me. This is not so that she can brush my hair or read to me from the latest tabloids (although that would be nice; I’d hate to have a brain bleed undo all my hard-earned knowledge of Kardashian genealogy); no, my sister will have a very specific and important job. She will be there to pluck my eyebrows.

Zoe, who is a nursing-school student, told me that hospitals actually have junior staff members who are hired to do this kind of thing—trim people’s nails, shave their beards, etc. But if she thinks she’s getting off that easy then she is sorely mistaken.

“How often do I have to come?” she’ll ask, glancing reluctantly at her iPhone calendar. “Once a week?”

“No,” I gasp. “Every three days for the eyebrows, and at least every week for the mustache.”

“You never said anything about a mustache,” she grumbles.

“Oh, and you’ll need to pluck three hairs from my chin once per lunar cycle. Two are very stiff and black, but one is freakishly long and white. You might have to poke around for it; it likes to hide.”

“Yay,” Zoe says.

Once she asked me what I would do if I got marooned on an island like the castaways from Lost, all of whom seemed to have clandestine access to spa-grade laser hair-removal devices and blow-dry bars.

“I’d bring tweezers,” I told her.

“But your bags went down with the plane,” she said. “You don’t have them.”

“I strapped them to my leg with duct tape. Or I’d sharpen rocks and use them as razors. Or fashion a jaunty niqab out of palm leaves.”

I am a girl with contingency plans.

I do realize that most people’s coma and plane crash preparations don’t involve brow shaping, but I happen to be a special case. My God-given eyebrows are so thick that they have become the stuff of legend, albeit among a relatively small circle of people who care about my forehead (a circle that now expands to include you, gentle reader, so welcome, namaste, please enjoy the complimentary boxed wine and Nair samples).

I also had a very impressive library.

I emerged from the womb on April 13, 1980, not only with a full head of black hair, but with a matching set of tiny but unmistakable caterpillars above my eyes. By the time I was six, the two had joined, forming a fuzzy bridge over my still buttony nose. Had I been born in the fifties, my mother might have burned them off with lye or sent me to Ms. Hannigan’s Home for Hirsute Girls, but unfortunately my parents were progressive idealists committed to raising confident children, and so blindly loved me the way I was. In the mid-1980s, the fashion and beauty industries had not yet begun targeting innocent prepubescent children, so I skipped happily into the great wide world totally unashamed of my Brooke-Shields-on-Rogaine look.

Neither of my parents has ever, to my knowledge, had a unibrow. My dad’s whole family is French and German, and they tend to be born blond, so they are absolved of blame. My mother’s father’s family, however, comes from Russia, a country known primarily for its vodka and excessive body hair.

That doesn’t seem to make sense, does it? I’ve always suspected my ancestors have conveniently excised some members from our family tree.

*Unconfirmed by genetic testing.

The moment I first remember being aware of my special genetic quirk was in fifth grade when a substitute teacher took over my class because our normal teacher, Mrs. Walling, had to have her gallbladder removed. I don’t remember what the substitute looked like, but I do remember that in the middle of a lesson he stopped and stared at me. He leaned forward, smacking his palms on his desk and breaking into a toothy grin, and said, without a trace of menace, “Young lady, you have beautiful eyebrows. Don’t ever pluck them!”

The whole class burst out laughing, and I sat there blushing in confusion and trying to figure out if the laughter was at me or at him.

Until that point I had never been made fun of for my eyebrows. I got teased way more about being a Goody Two-shoes (and for peeing in my woolen tights this one time during a spelling quiz in third grade, and not changing out of them because I thought no one would notice, and having my friends make up a song called “Una Has a Butt That Smells Like Pee”). I know they weren’t all blind, so I can only assume they were just

distracted by my braces and fetching wardrobe, which relied heavily on leggings, cowboy boots, and oversize tie-dyed T-shirts. Maybe, since I’d moved from Austin, Texas, in 1988, my Brooklyn classmates just thought Texas grew ’em bigger.

That substitute teacher was just the first of many strangers to comment on my appearance. I suppose I should feel lucky that he was so kind. I’m glad my first taste of ridicule didn’t come from the man who did a double take on the street and jabbed at his friend to gawk, or the group of Asian teenagers on the subway who kept shouting “Freak!” and then bursting into laughter, or the pervy photographer who said he wanted to take my picture because I had such an “interesting face.” I took to putting my hand up to my forehead in public places, as if I had a permanent itch right above my nose. It wasn’t subtle, but it was acceptable camouflage.

The saddest thing about my unibrow is that it would have been so easy to fix. I mean, it’s sort of ridiculous, given how much it came to stress me out. It’s not like I had something that defied medical science, like an extra head from an absorbed twin, or even a surgical problem like a vestigial tail or third nipple. Literally the only thing standing between me and the end of my suffering was a six-dollar pair of tweezers (which, come to think of it, probably only cost three dollars in 1992—I could have used one week’s allowance and still had two dollars left over to spend on decoupaging my vanity with Brian Austin Green centerfolds from Tiger Beat). I don’t know why I didn’t do anything about it sooner, but after decades of obsession I’ve developed two theories.

Theory 1: I Was Confused as to Which Decade I Was Living In

Like No Other

Like No Other Five Summers

Five Summers Don't Fail Me Now

Don't Fail Me Now You in Five Acts

You in Five Acts Unabrow

Unabrow