- Home

- Una LaMarche

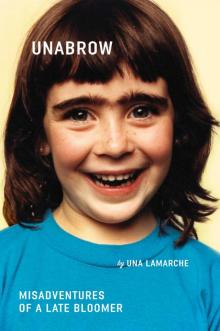

Unabrow Page 2

Unabrow Read online

Page 2

There is actually a frightening amount of evidence to support this. Growing up, my parents only had a thirteen-inch black-and-white TV. The first cassette tape I ever bought was KC and the Sunshine Band’s Greatest Hits. (In case you’re wondering, this is not a cool answer to give when someone asks about your first adolescent musical experience.) In eighth grade, I took to wearing prairie skirts and love beads. A popular girl in my class once asked me, point-blank, “Why are you wearing that?” and I’m pretty sure I just shrugged and pointed to the swirly peace signs adorning my polymer clay bead choker.

Theory 2: My Mom Was Sort of a Hippie

There’s even more evidence to support this: She went to art school in the mid-sixties. She was at the March on Washington. She worships Bob Dylan. She didn’t (still doesn’t) shave her armpits. She keeps pictures of herself from the seventies wearing metal headdresses and fright wigs. She sent me to a Waldorf kindergarten, where I was forced to make dolls out of corn husks. She claims that no one should sleep in underwear because their genitals “need to breathe.” Not exactly the poster girl for our country’s self-flagellating adherence to cultural stereotypes of femininity, which I appreciate as an adult but could have done without back then. Also, since my dad had a beard and mustache at the time, there may well not have been a single razor in the house for the duration of my pubescence.

That said, it was my mom who eventually introduced me to tweezers. It happened on a weeknight, in our living room. I was fourteen and had finally confessed—to my great shame—that I did not feel beautiful in my natural state, no matter how many times my parents loudly assured me that I was, and that they were not just saying that because they were blinded by familial love, or perhaps the glint from my glitter retainer. She sat quietly for a minute and studied me with sad eyes.

“Would you like me to shape them for you?” she offered. I nodded mutely and then perched on a stool while she went to retrieve the necessary tools from her fireproof safe or wherever she had been hiding them. As she went to work, tears rolled down my face, as much from relief as from the stinging pain. When my mother was done, she held up a hand mirror, and what I saw took my breath away. I had a one-inch gap between the thick, wild, wiry mess on my forehead. I had eyebrows, plural. It hadn’t felt that good to finally have two of something since my right boob had grown in.

Of course, what I hadn’t considered was that the only thing worse than being made fun of in junior high was to make an abrupt physical change immediately visible to all your peers. The next day, everyone asked about my eyebrows. It was a straightforward enough question: Did you pluck your eyebrows? But for some reason I refused to admit it. I said no, that I had simply been trimming my bangs and “missed.” I tried to seem nonchalant, but it didn’t help that I did not actually have bangs.

The naked strip between my eyes was world expanding, a follicular gateway drug. Shortly thereafter, my mother took me with her to a salon that did brow shaping, in the hopes that we could achieve something better than two thick rectangles. The aesthetician had no idea what she was in for; I could see shock and fear in her eyes as I approached from across the room. But she gamely took on the challenge, chipping away slowly until she had transformed my sloppy dashes into two commas, floating across my forehead like stocky little sperm. On the floor beneath my chair, it looked like I’d had a haircut.

I coasted on my new double brows for a month or two, but eventually I took matters into my own hands and got hooked on plucking. At first I just dabbled, kept them looking neat, experimented with shapes and varying degrees of thickness. But as I neared the end of high school, I rebelled, slowly deleting my eyebrows until they became almost invisible. I tried to be stealthy, but it was about as subtle as Chris Christie suddenly wasting away from anorexia. My mother noted this transformation with frightening dedication, and we started having the kinds of conversations you would normally see on a cautionary Afterschool Special, if they made them about really insignificant physical traits.

“Honey,” she said hesitantly as she made dinner and I did homework at the kitchen table, “I’m worried.”

“Mo-om,” I said. “I’m fine. Don’t start.”

“You look sick.” Her eyes brimmed with tears. “Like Whoopi Goldberg.”

“Whoopi isn’t sick.”

“Doesn’t she have cancer?”

“No!”

“But, sweetie, she has no eyebrows.”

“Because she shaves them off, Mom. Which is her choice.”

“Well, I think it’s awful. You know, when I was your age—”

“Mooooooom, stooooooooop.”

“—I had gorgeous, thick eyebrows like you. And then I overplucked and now . . .” Her breath caught in her throat and she set down the organic pepper she was chopping. “Honey, they don’t even grow anymore. I have to use a pencil.”

When I failed to respond, it only made her angry.

“You don’t know what you’re giving up!” she yelled. “You’re only sixteen. You have your entire life ahead of you!”

“Shut up! You can’t tell me how to conduct my own personal grooming!” [Cue angry teenage flounce out of room.]

My mother was never a stage mother—unless that stage was my forehead. She was counting on me to live her shattered dream, so I’m not surprised that she was sad to see the unibrow go.

“Una’s eyebrows are too thin, don’t you think?” she once asked my ninth-grade science teacher during a PTA conference. She seemed convinced that if she couldn’t change my mind one-on-one, she could beat me through polling.

In tenth grade I humored her, dressing up as Bert from Sesame Street for Halloween. Even the yellow face paint, orange nose, and blood dribbling down my chin (Bert was also a zombie) didn’t put her off; she thought I looked gorgeous.

Physically, my unibrow problems have been over since junior high (give or take a few plucking lapses due to illness), but now that I’m a mother I’ve shifted my eyebrow focus to the fate of my son and his potential future siblings. For someone who once put on a Greenpeace T-shirt and asked strangers to save the whales (albeit under duress—see page 193), I devote a truly astounding amount of time to thinking about hair removal for young children. I obsess over the best way to handle the inevitable genetic legacy that I will pass on to my kids. For instance, does creamy infant skin react poorly to depilatory creams? What’s more emotionally scarring: school yard taunts, or electrolysis in the second grade? Can you actually shave off a child’s unibrow under the pretense of trimming his bangs?

Of course I’m not actually going to forcibly wax a toddler. Any halfway serious plots I had got tossed when one of MTV’s Teen Moms plucked her sleeping three-year-old’s unibrow in 2013, raising media pitchforks. That’s it, I told myself sternly, I cannot share the parenting philosophy of an eighteen-year-old who already has a chin implant and a sex tape. How would I have turned out if my mother had been a press-hungry reality star instead of the kind of person who took naked outdoor showers on vacation, even when we had guests?

I want to be prepared for the talk about the Big U, so I did what any brain-atrophied, digitally dependent millennial would do: some half-assed research on the Internet. And here is what I discovered: having a unibrow is actually a condition called “synophrys.” Isn’t that cute? I even thought of calling this essay “Synophrabulous!” but I didn’t think anyone would get it. Anyway, there’s not much about synophrys on the World Wide Web—if you can believe it, no one has ever thought to write a cultural history of unibrows. Most of the entries say things like:

The unibrow conventionally has negative associations in western [sic] culture, and is the reason why many people remove excess hair between the eyebrows*

Oh, really, Internet? No shit, Sherlock. Here’s a slightly more surprising take:

If you have a unibrow you probably have tons of testosterone and a large penis.*

&n

bsp; Why, thank you, kind sir! No hot dog here, but quite frankly, if I have too much testosterone, that would explain a lot more than my eyebrows. It would shed some light on why I chopped off my hair and insisted on playing with He-Man figures as a child, or why I was the only girl in my preschool class to cross heteronormative lines on Halloween by dressing as Peter Pan. Sadly, it would not explain the Donnie Wahlberg doll I purchased circa 1990, at the height of NKOTB mania. If I am really a man, I must be gay.

But let’s assume for a minute that we’re talking about a natural-born, estrogen-filled, penisless woman who just happens to have the facial hair of Early Man. Surely there must be some place on earth where this is not accepted as an automatic cause for mockery? Aha!

In some non-Western cultures this facial hair does not have a stigma, and may even be seen as a sign of feminine beauty, as in Russia or in Iran, where connected eyebrows are a sign of virginity and a large dowry of goats.*

That’s interesting. Jeff, my husband, is third-generation Armenian American, which places his ancestors right between Russia and Iran (a fact he had to inform me of, as I am worthless at geography). While I didn’t have a unibrow when we met, maybe he could sense it there, like a phantom limb, and heard the voices of the elders whisper, “This is the virgin for you.” Unfortunately, I suspect, the correlation between synophrys and celibacy is one of cause and effect. (He also got screwed on the goats.)

There’s a book I found called The Eyebrow by Robyn Cosio, who, somewhat unsurprisingly, had a unibrow as a young woman. There is a reason that all the trainers on The Biggest Loser were invariably fat as children; emotional scars are best scrubbed clean by attempting to educate others about your affliction. Anyway, Ms. Cosio writes—without a footnote—that in ancient Greece:

An eyebrow that marched in a single line, from one edge of the right eye, over the nose, to the edge of the left eye . . . was prized as a sign of intelligence and great beauty in women. If a woman was not blessed with one very large and very thick eyebrow, she was allowed to close the gap between her eyes with paint made of coal or lampblack. Or she simply put on false eyebrows.

Oh, Robyn. Ye of the selfsame name as my favorite Swedish pop star. Why must you taunt me with this imaginary utopia, in which I could have been the Angelina Jolie (or, okay, let’s be realistic—the Marcia Gay Harden) of Sparta? I never had this knowledge growing up, and since most Americans with unibrows are villainous cartoon characters, my only positive role model was the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Kahlo famously exaggerated her unibrow and visible mustache in her paintings of herself, which some art buffs interpret as deliberately unflattering.

Purposefully unflattering or not, Kahlo remains the sole icon of female unibrow self-acceptance. One of her most famous paintings, her 1940 Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace, Hummingbird, and Unibrow, acknowledges it outright. That is actually a really good idea; I might steal that from her. Instead of seeing my old photos as unflattering relics, I can turn them into art. My twelfth birthday party will heretofore be known as Self-Portrait with Oversize Denim Hat, Slap Bracelet, and Unibrow.

“I clipped an article for you from the Times magazine,” my mother announced the other day. She handed me a folded piece of glossy paper with a look that seemed awfully smug for someone who still cut articles out of magazines with scissors instead of forwarding an e-mail link like a normal person. “Thick eyebrows,” she said, “are back in.”

I smiled and thanked her, tucking the clip into my pocket. I didn’t have the heart to tell her that when people in fashion say “thick,” they don’t actually mean thick. These are the same people who hold up Anne Hathaway—whose breastbone can be seen from space—as an example of a “curvy” body type. So when they say that thick eyebrows are suddenly “in” again, they are basically joking. They are not inviting the women of the Caucasus to come and pose on the cover of Vogue, and I’m both relieved and surprisingly embittered by this. It’s very confusing to define so much of your inner identity by an exterior trait you no longer possess. (Jennifer Grey, if you’re reading, I know you feel me on this.)

I would like to be a more unself-conscious person and to let my freak flag fly right in the middle of my face. I also wish I could discover a stray chin hair without screaming, “Don’t look at me!” to an empty house and then pratfalling into the bathroom with a pillow clutched over my face. I wish I could imagine a desert island scenario in which I was not frantically searching for sharp rocks with which to jab at my forehead, but rather enjoying the sun and, hopefully, having a tryst in a waterfall with Sawyer. But if wishes were horses, then beggars would ride—and I would have to get over my phobia of their enormous Chiclet teeth.

So I’ll probably just continue to make endless self-deprecating jokes about my unibrow until I die or I slip into the coma that haunts my sister’s nightmares. Because being loud about it is the only way that I know how to find other members of my tribe: yet-to-peak former outcasts with the dreaded “good personality” of the previously homely. I just don’t feel safe otherwise. I mean, I can’t trust anyone who never had an awkward phase in high school.

Those people are the real freaks.

THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS OF DIY BANGS

We’ve all been there.

It’s a weekend afternoon. Your parents/roommate/spouse/children are out doing something productive and you are sweat-stuck to the couch, wearing a top or pants but definitely not both.

You think about taking a shower. You walk to the bathroom, because when it comes to personal grooming, showing up is half the battle. (The other half of the battle is remembering to shave both legs, and then return your parent’s/roommate’s/spouse’s razor to its cradle without any visible hairs.)

But before you even make it to the shower, you see your reflection in the bathroom mirror (sin #1) and make a horrified face, à la Dr. Kimberly Shaw when she dramatically tore her wig off on season two of Melrose Place. Only you, sadly, have no wig to remove; you have not recently faked your own death, and that is your real hair.

What can I do to instantly improve my appearance? you ask yourself. You look around for tools. There’s a toilet plunger, which would probably only make things worse. There’s a toothbrush, which is no help because you’ve already uncorked the wine. Your eyes fall on a Walgreens brand mud mask that you purchased sometime in 2007, and even though it has hardened to an impenetrable solid, you reason that it might be difficult to knock yourself unconscious with it on the first try. And that is really your best choice because you look like Tom Hanks in Cast Away . . . after he lost Wilson. Yeah, it’s bad.

It is only then, in an emotional state best described as “umbrella Britney,” that you see the scissors. They’re nail scissors, but hey, tomato, to-mah-to, right?

I don’t know when bangs became such a facial game-changer. I think we can safely blame Zooey Deschanel, who seems to have had a falling-out with the real estate above her eyeballs circa the mid-aughts. (Worshipping false bang idols like Deschanel, Taylor Swift—and even, Bo forgive me, FLOTUS—is sin #2!) But we all secretly think we would look good with bangs. And so, without fail, you—the you who has neglected to take care of basic needs like bathing or wearing both tops and bottoms—become convinced that not only do you need bangs, but you are capable of cutting them yourself (sin #3).

You can totally do this, purrs the slovenly, pantsless devil on your shoulder. Remember the last time you got your hair cut? It was so easy; you don’t need to pay anyone. Just pull the hair straight up, snip, and loudly speculate as to whether Stacy Keibler was George Clooney’s beard.*

Ugh, she totally was, you think, as you pick up the scissors (sin #4). She is a retired professional wrestler who was on Dancing with the Stars, for God’s sake. She wasn’t even a beard; she was a Billy Bob Thornton soul patch.

You fold some of your hair over your forehead and mug for the mirror. You pretend you are Katy Perry at the VMAs and that

you are wearing a bra made of gummy bears. Yes, you think, I can totally rock bangs.

Totes McGotes! cries the devil on your shoulder.

You hold the hair out in front of you, obscuring your vision. You snip (sin #5), visualizing a sexy, openmouthed Jennifer Garner (sin #6; no one looks sexy that way in real life).

You examine your handiwork and find that you have cut at a forty-five-degree angle from your left eyebrow to your right earlobe. You cut again. This time you’ve gone too short on the right side. Maybe I should quit while I’m ahead and go to a salon, you think, a cool breeze of sanity that blows right through your ears.

Then you remember that you still have to shower and shave and either wash or set fire to the sinkful of dishes before your parents/roommate/spouse/children return. You soldier on (sin #7a), snipping away like a sculptor trying to reveal the masterpiece trapped in a block of marble.

This is just one example of “sexy open mouth” gone wrong.

And five minutes later, you step back and look in the mirror (sin #7b), to reveal your new, inch-long fringe.

It is your David, your Mona Lisa, your rheumy-eyed portrait of an elderly Kate Middleton. It is your eight-months-early Halloween costume as Lloyd—Jim Carrey—in Dumb and Dumber. And it is entirely your fault.

Remember, only you can prevent the devastating side effects of unprotected banging. Be smart. Stay safe.

What’s Happening!! . . . to My Body?

By the time I was six years old, I had given birth multiple times.

It always started in a plastic hamper I referred to as my “dress-up closet,” where I would select the perfect kimono for what I knew was sure to be both a physical and an emotional ordeal. I knew this because my mother, who taught childbirth education classes, had let me watch a VHS tape called Birth in the Squatting Position, which taught me that (a) babies usually came out looking like angry Smurfs and (b) giving birth involved a lot of wincing, moaning, and writhing around while holding what looked like a wet coconut between your legs. It was a young actress’s dream role.

Like No Other

Like No Other Five Summers

Five Summers Don't Fail Me Now

Don't Fail Me Now You in Five Acts

You in Five Acts Unabrow

Unabrow