- Home

- Una LaMarche

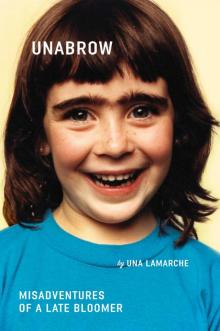

Unabrow Page 7

Unabrow Read online

Page 7

Once upon a time, I belonged to a gym. Actually, technically it’s thrice upon a time, since I managed to join and quit three different gyms. I do not like going to the gym—I don’t like waiting for machines or being self-conscious about my ratty gym clothes or attempting to shower behind a tissue-thin curtain that does not go all the way to the wall on either side—but I am vain, so for a long time I figured a gym membership was a necessary evil if I wanted to keep fit. My first gym, right out of college, turned out to be too expensive to afford on my nonexistent salary. The next one was cheap but too far from home, so I never went. Then I got a job that came with a free gym membership. And it all would have worked out beautifully if it wasn’t for Clive, a sexy personal trainer who approached me on my first day and coerced me into spending twelve hundred dollars on a dozen sessions. (By “coerced,” of course, I mean “asked me if I wanted to,” as I am incapable of saying no to anyone, ever. Especially if they look like a black John Krasinski.) I charged the sessions on a credit card and stocked up on ramen noodles for the coming famine. I have to admit that during those three months, I loved the gym. I looked forward to my workout each week, especially the stretching part when Clive would lean on me and push my legs back over my head. When my sessions ran out Clive assumed I would sign up for more, but I couldn’t tell him that I was broke, so I quit the gym to avoid him. He called me once to try to change my mind and I lied and said I’d lost my job.

Since I can no longer show my face at any gyms in the metropolitan New York area, over the years I have amassed a small library of fitness DVDs. Jeff calls the stash my “porn,” which is inaccurate—if they actually were porn I would watch them way more often. As it is I only use a few—the ones that require the least effort on my part. It’s telling that my favorite video is The Girls Next Door Workout, which stars three of Hugh Hefner’s former Playboy Mansion girlfriends. The ladies’ buoyant chests and tight outfits prevent them (and, by extension, me) from doing anything too strenuous, and their shining, Barbie-blond pigtails and bright smiles lull me into a trance so deep that I barely realize I’m moving.

A few years ago I also purchased Nintendo’s Wii Fit, mostly because it seemed like the perfect workout regimen for someone who needs to be distracted (in this case, by a video game) in order to exercise. Unfortunately, after only a few uses I was forced by vanity to shove the system under the couch and cower in fear. For instance, no one had told me that if I did not use it every single day, the Wii would chide me as soon as I started. “Oh, too busy to work out yesterday?” it would mock in a high-pitched, childlike voice not unlike 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL after a few hits of helium. I don’t know about you, but standing in front of my TV wearing a sports bra is a vulnerable position for me. Being mocked in that state sends me into the kitchen for some ice cream and/or vodka. Also, before each exercise, the Wii would ask me to step onto a balance board so that it could weigh me and register my alignment. For some reason, half the time when I stepped on, the voice would say, “Okay!” but the other half of the time it would exclaim, “Oh!” Like, “Oh! Wow! We’ve got a big’un! Send in the reinforcements!” A year and about a dozen workouts after I bought it, I sold the Wii Fit for half of what I paid, and used the profits to purchase an iTunes Season Pass to Living Lohan.

Oprah Winfrey is famous for her “aha! moments,” flashes of enlightenment or emotional breakthroughs, which the big O seems to have with the regularity that most people move their bowels. I’ve had my very own aha! moment. In the fall of my senior year of high school I realized how much I hated fitness and how far I was willing to go to avoid it.

On that fateful day, I was sitting on the uptown 1 train to Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, reluctantly on my way to a cross-country track meet. As usual, I was terrified.

Simply put, I hated track. I hated everything about it. I hated running, for starters. I hated competition. I hated stripping down to my flimsy purple short shorts—seemingly cut so as to enhance and encourage saddlebag jigglage—in the chill of November and waiting for the gun to go off to signal the start of the race. I hated feeling my lungs burn and my hamstrings cramp and swallowing my own coppery saliva. I hated the way my legs went all rubbery as I neared the finish line, reducing me to the speed and acuity of a milk-drunk toddler. Most of all I hated the actual running part. Sitting on that subway train, filled with dread, I realized I had to do something to get myself out of the race—and off the team—for good.

I had only joined track in the first place because my friend Rachel convinced me it would be a good character-building exercise. Up until sophomore year, my extracurricular activities had been limited to art club and a local musical theater class composed mostly of twelve-year-olds. I had the pasty, black-and-white complexion of Peter Lorre in M. Rachel, by comparison, was almost six feet tall and built like a tree. She played a different sport every season. She glowed with health. I don’t know what I was thinking, listening to her. I guess I hoped that running would change me as a person. I clung to the belief that it might sprout me up a few inches, turn my chalk-colored skin a healthy peach, and form sinewy muscles out of the soft, fatty pads of my calves and upper arms, which were so undeveloped that neighbors probably suspected that my parents were raising me for veal.

I should have known that I was kidding myself. Genetically—and I’m certain this could be backed up by a blood test—I am at an athletic disadvantage compared to most of the world’s population. I come from a family that has churned out successful musicians, businesspeople, artists, and writers, but put up a volleyball net at one of our reunions and you’d think someone had called in a bomb threat. It is a true story that my father, who was captain of his high school debate team, once put his back out changing a roll of toilet paper. I was never forced (or even encouraged) to play competitive sports as a kid, but somehow I must have intuited my lack of ability because I soon came to live in fear of them. As early as first grade, I used to make myself physically ill over whether I would have gym class on any given day. To calm my nerves, I’d make my dad ask my teacher about gym day when he dropped me off. On one memorable occasion, after she said no and I relaxed as my father turned to leave, Ms. McHenry corrected herself.

“I’m sorry, Mr. LaMarche,” she said, “I was wrong; Una does have gym today.”

I promptly burst into tears.

When my family moved to New York and I started at a new elementary school, my fledgling fear became more of an acute phobia. Suddenly I had two gym teachers: Mr. Hyman—short, stocky, white, and loud, with reddish hair that matched his constantly flushed face—and Mr. Bolden—tall, muscular, reticent, and black, with heavy-lidded eyes and an ever-present basketball wedged in the crook of his elbow. They were always together, sort of like Ernie and Bert crossed with Riggs and Murtaugh from Lethal Weapon. Twice a week, our class would file into the gym in our maroon-and-urine-accented uniforms and sit cross-legged in rows.

The games Hyman and Bolden forced us to play ran the gamut from farcical to torturous. Sometimes we’d push a giant beach ball across the room for no reason; other days they had us doing timed sprints around the school yard or hanging limply from the chin-up bar as Mr. Hyman barked, “Don’t just hang there; pull! Use your arms, for Christ’s sake.” The one sport I wasn’t completely embarrassing at was something called scooter soccer, a game seemingly designed to handicap everyone. The essential rules of soccer were the same, except that instead of standing or running, we sat on little squares of plastic with wheels. Since this was public school in the 1980s, the wheels were often warped and in order to move at all we had to pound the floor furiously while pushing backward. In retrospect I liked it not so much because I was good at it, but because no one else was.

But as terrified as I was of gym pretty much all the time, I was never more nervous than on the days that we played a game Mr. Hyman called “basketball.” For the record, it wasn’t basketball. As athletically challenged as I am, I k

now how basketball is played. (Sort of.) No, this was what basketball would have been in Lord of the Flies—a sudden-death gauntlet aimed at weeding out the uncoordinated. The class was divided into teams and counted off so that everyone had a nemesis on the opposite side of the gym with the same number. Two basketballs were placed in the center of the floor, and we crouched on either side, some literally vibrating with excitement, others just willing our bladders to be strong. Mr. Hyman would stand at the front of the room and shout in his thick New York accent—“Numbaaaaaaaaaaah . . . five!”—and immediately two kids would sprint to the center, grab the basketballs, and start shooting for the basket. At that time I was less than five feet tall, weighed about sixty pounds, and had truly horrible aim. My utter failure wouldn’t have been so humiliating if not for the fact that we were not allowed to sit back down—even if the competition had made their shot on the first try—until we made a basket. I would stand there for what felt like hours, heaving the ball with both hands toward the net, sometimes missing even the backboard.

The cruelest part, looking back, was that I was too young to know that Hyman was a funny last name.* I know it probably wouldn’t have changed anything that came after, but I still like to imagine my skinny, prematurely hairy adolescent self spinning on her Reebok high-top-clad heel and dropping her basketball with a dramatic sneer, saying, “Yeah, I suck at basketball. But at least my last name isn’t part of a vagina.” Then all my classmates would slow clap. (Incidentally, slow clapping during fantasy revenge monologues is probably my best adult sport.)

Fast-forward to high school, two awkward gym uniforms, and one retainer later. Seeing as my hands and eyes were still about as coordinated as an epileptic busboy’s, and since I had Rachel as my enabler, I decided that track was my only option if I was ever going to get into something as wholesome as extracurricular organized sports. The big selling point for me was that the sole requirement for eligibility was the ability to remain upright while moving forward. To excel, of course, you had to be strong and fast, but to be a member of the team all you had to do was show up. My high school was a magnet school for math and science and attracted the types of kids who begged Santa for new graphing calculators. Jocks were in short supply.

It didn’t take long for me to realize I had made a mistake. On my very first day I had to run a timed loop of the Central Park Reservoir—just over a mile and a half—under the supervision of the coach, whom I’ll call Ms. Patchman. (I’m changing her name because I’m sure I’m about to exaggerate her awfulness—she scared me so much that she lives in my memory as a cartoonish killjoy, some cross between Nurse Ratched and Clint Eastwood in Million Dollar Baby.) Ms. Patchman was tiny but imposing. Scrawny and shriveled, she wore her hair in a close-cropped, wispy Afro the color of rusty tap water. I had heard rumors around school that she was a “lesbo,” but she did not seem to like girls, or anyone, for that matter. Me especially.

When I arrived at the reservoir entrance, she narrowed her eyes and nodded once in weary acknowledgment of my presence.

“Ever run this far?” she asked. I mumbled that I had not. She considered this for a moment and then sighed. “If you vomit,” she finally said, “try to do it off the main path.” I like to think that it’s to my credit that I didn’t throw up until I got home that night.

I started group practice the following day and found that there was safety in numbers. Running with the rest of the team allowed me to study and imitate them, as if I were doing field research on an alien race. There were a few slower girls I could keep pace with, and I carefully pumped my arms and kicked my legs along with them. I learned how to run through a “stitch” by pinching the muscle and breathing deeply, and even if I didn’t have one I would mime one every so often just to seem legit to the Japanese tourists snapping photos along the reservoir path. I also learned a lot about Ms. Patchman from the other girls. Legend had it she had once been a great runner but had injured her knee and had to retire. They were all pretty sure that she didn’t wear a bra, but none were willing to do the kind of research necessary to find out definitively. She had once chaperoned a school dance wearing a bolo tie and blew a whistle when kids started slow dancing to “November Rain.”

Ms. Patchman kept her office in our high school’s basement with the rest of the physical education teachers and encouraged us to visit for one-on-one performance reviews, but I couldn’t bring myself to go. Not only was I already terrified of her, but I had also unintentionally flashed one of her colleagues, Mr. Mistriel, during an eighth-grade swim class in which I opted for a floral cotton suit with a sweetheart neckline instead of my more trustworthy Speedo. I had propped myself up on the lip of the pool to ask a question, and when I looked down I saw that the neckline had stretched below my rib cage. The thought of accidentally running into the man who had seen my awkward, fledgling nipples was more than I could bear.

Since I was a terrible runner, it was pretty easy to avoid interacting directly with Ms. Patchman; she spent the vast majority of her time training and tending to the good runners on the team. The slow runners were treated with a mix of apathy and disgust, like we were stray cats peeing in the hay reserved for her thoroughbreds, and she eventually separated our workouts from those of the varsity girls’ so that we wouldn’t slow them down. Not that we minded. All of us in JV were thrilled that we hadn’t raised anyone’s expectations of our abilities; in fact, we kept them low on purpose. One spring, I accidentally won an eight-hundred-meter race by inadvertently joining the slowest heat, made up of the types of people who carry inhalers and wear strapped-on goggles. You should have seen Ms. Patchman’s face when I crossed the finish line—I think she almost smiled. As I collected my medal I cursed myself for having done well enough to get her attention, but then the next week I tripped over a hurdle and the universe righted itself again.

Unfortunately, no amount of underachieving could exempt me from the weekly 5K races that were part of fall’s cross-country schedule, which was how I found myself on that uptown train senior year, my muscles tense and my stomach in knots, trying to find a way out. A braver person would have simply marched over to Ms. Patchman—who was sitting alone at the opposite end of the subway car—and quit then and there, but I was too afraid. A healthy respect for authority figures combined with a near-evangelical devotion to conflict avoidance led me to believe that telling my coach that I wanted to quit the track team would be like a made man telling Vito Corleone that he wanted to stop whacking people. I fantasized about Ms. Patchman ripping my uniform off my body with her bare hands and then marching me up to the registrar’s office and demanding that I be expelled. The next morning I might wake up to find a lacerated sneaker under my covers, reservoir mud seeping into my sheets, and then I’d have to change schools and use my mom’s last name, and maybe even get a nose job before I’d stop having nightmares about waking to find her standing in my doorway with a starter gun aimed at my forehead.

Oprah says that an aha! moment is like a lightbulb turning on in your brain, but mine was more like a floodlight. All of a sudden I had the answer, a way to get out of running without quitting, a solution that would grant me an honorable discharge from my own personal hell.

All I had to do was to hurt myself. Badly.

The five-kilometer course at Van Cortlandt Park takes the charming shape of a dandelion blossom spilling out of a dented tin can. The start and finish lines are located a tenth of a mile or so apart on a vast expanse of balding grass known as “the Flats.” The first mile is run in full view of onlookers; when the race starts, runners head south in a thick pack and make two left turns, essentially forming the bottom of a square, before veering off onto a dirt road called “the Cow Path” (named for the—surprise!—actual cows that grazed there before the Van Cortlandt family donated the land to the city). Then, mercifully, thick woods hide the beet-red faces and jiggling thighs from view as runners advance toward the more treacherous terrain of “the Back Hi

lls.”

I knew that I could not stage my fall on the open plains of the Flats or the soft incline of the Cow Path; I needed a good, steep downhill slope, preferably dotted with loose, jutting rocks and toe-catching tangles of dead branches. Ironically, the adrenaline in anticipation of my painful freedom caused me to run the first mile faster than ever, and to the casual observer I’m sure I must have looked relaxed and confident, like a really, really slow white version of Flo-Jo. Little did they know that, instead of humming the Chariots of Fire theme music or focusing on my breathing, I was trying to calculate the angle of impact at which I might be able to twist an ankle without actually breaking it. I wasn’t after real pain and suffering, after all; I just wanted a sob story that would get me out of gym. I thought of my best friend, Anna, who as a child had coveted a friend’s plaster cast so passionately that she attempted to break her own leg with a hammer. “I remember holding it in the air with both hands,” she told me later, “but I just couldn’t bring myself to do it.” She found it easier to “accidentally” fall out of her bunk bed, but ended up with nothing more than a black eye, courtesy of a turret on her She-Ra Princess of Power Crystal Castle. She didn’t even get an eye patch.

Approximately a mile and a half into the Van Cortlandt 5K course, runners come to a small, graffiti-covered footbridge that crosses over the Henry Hudson Parkway and serves as the de facto entrance into the Back Hills. On a map, the Back Hills form a rough circle that resembles a nubby, fetal fist waving hello, but on the ground they are far more menacing. (Wikipedia even calls them “infamous,” and Wikipedia’s seen it all.) The Back Hills go on for almost a mile and a half and are the last leg of the race that’s run under cover of woods. So I knew that in order to carry out my plan, I had to throw myself down one of them.

Like No Other

Like No Other Five Summers

Five Summers Don't Fail Me Now

Don't Fail Me Now You in Five Acts

You in Five Acts Unabrow

Unabrow